Black Women Mystics (a worthy focus in this time of heightened racism)

Tuesday, July 30, 2019

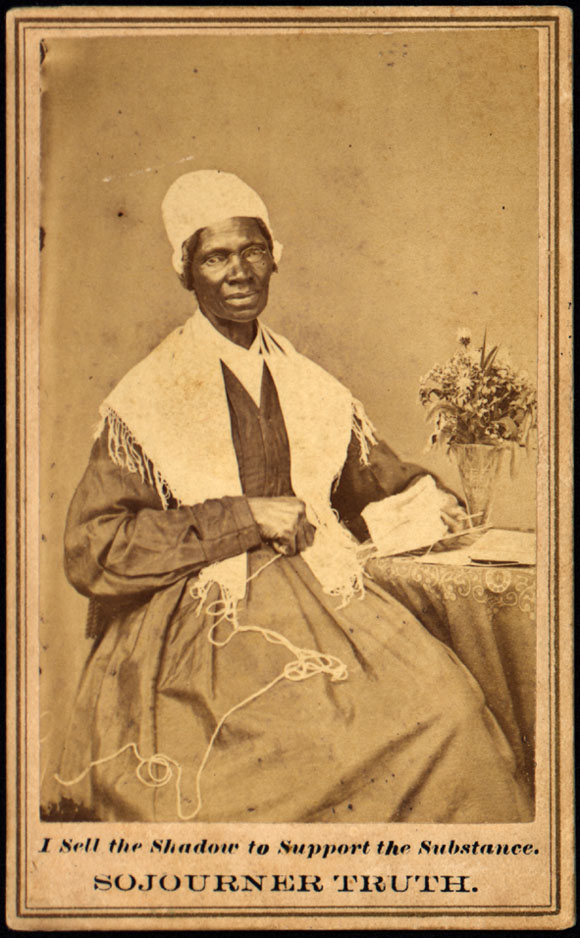

Mysticism is not all ecstatic visions. People who have endured great suffering and let it open them to a new consciousness or perspective are often mystics. They discover that they are always sustained by Love’s presence. James Finley has a beautiful image for this unceasing support: Imagine, if at the count of three, God would stop loving you into your chair; at the count of three, your chair would be empty. Moment by moment you are loved, chosen, invited into being. So lived Sojourner Truth.

Sojourner Truth (1797–1883)—an abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights—was born “Isabella” to an enslaved couple in New York. When she was nine, Isabella was sold to another slave-holder that brutally beat her. Joy Bostic describes how Isabella’s mother taught her children strategies to survive “within the oppressive system of slavery. Mau-Mau Bett would sit with her children during the evening under the stars and teach them how to call upon God to help them in times of crisis.” [1]

Isabella gradually came to know God as what I might call “the eternal now,” beyond human comprehension. God is only known by loving and experiencing God. Sojourner Truth wrote of her own mystical encounters with God in the third person:

As soon as Isabella saw God as an all-powerful, all-pervading spirit, she became desirous of hearing all that had been written of him, and listened to the account of the creation of the world . . . with peculiar interest. For some time she received it all literally, though it appeared strange to her that ‘God worked by the day, got tired, and stopped to rest,’ . . . after a little time, she began to reason upon it, thus—‘Why, if God works by the day, and one day’s work tires him, and he is obliged to rest, either from weariness or on account of darkness, or if he waited for the “cool of the day to walk in the garden,” because he was inconvenienced by the heat of the sun, why then it seems that God cannot do as much as I can. . . . If I had been God, I would have made the night light enough for my own convenience, surely.’

But the moment she placed this idea of God by the side of the impression she had once so suddenly received of his inconceivable greatness and entire spirituality, that moment she exclaimed mentally, ‘No, God does not stop to rest, for he is a spirit, and cannot tire; he cannot want for light, for he hath all light in himself. And if “God is all in all,” and “worketh all in all,” as I have heard them read, then it is impossible he should rest at all; for if he did, every other thing would stop and rest too; the waters would not flow, and the fishes could not swim; and all motion must cease. God could have no pauses in his work, and he needed no Sabbaths of rest. Man might need them, and he should take them when he needed them. . . . As it regarded the worship of God, he was to be worshipped at all times and in all places; and one portion of time never seemed to her more holy than another.’

References:

[1] Joy Bostic, African American Female Mysticism: Nineteenth-Century Religious Activism (Palgrave Macmillan: 2013), 70.Sojourner Truth, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth (Digireads.com Publishing: 2018), 64-65.